Natural Language Explanation (1) - Methods

Introduction

Deep learning has long been criticized for being opaque, making it challenging to establish trust in sensitive domains like medicine. People have therefore sought ways to allow neural networks to generate explanations for their predictions to help users better understand models and make decisions. There are two common ways to generate explanations for NLP models: 1) rationale extraction that extracts salient segments of the inputs responsible for the model’s prediction; 2) natural language explanation generation that generates free-text explanations for the model’s prediction. This essay will mainly focus on the latter route, and I’ll first summarise the development of methods (according to my current reading) and leave the discussion of evaluation (which is also an interesting topic) to another piece of work.

Typical Training Paradigms and Variations

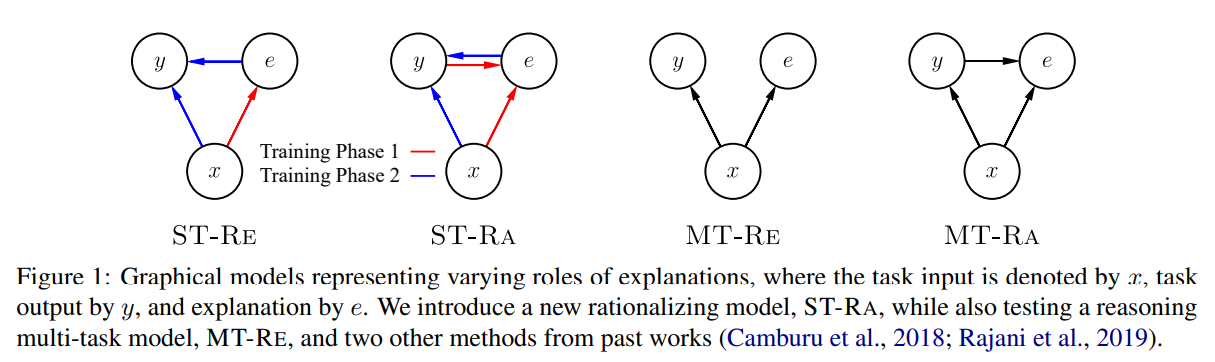

Hase et al. (2020) summarise the NLE (natural language explanation) generation methods as four graphical models, which indicates the typical training paradigms for NLE generation, and we will follow this to start the introduction.

Figure 1. Typical training paradigms as graphical models.

As shown in Figure 1, Hase et al. (2020) divides the generation of explanations into the reasoning(RE) mode and the rationalizing(RA) mode. For the RA mode, the generation of explanations is explicitly conditioned on the labels, while for the RE mode, the generation of explanations is provided only with input. The learning of label prediction could also be divided into two modes, where for the single task(ST) mode, the explanations are part of the input for the task model, whereas, for the multi-task(MT) mode, the explanations serve as additional supervision in a multi-task training objective. Four modes can thus be obtained by combination. Among them, ST-RE and ST-RA are pipeline methods, and MT-RE is end-to-end, while MT-RA although can be trained jointly, its inference has to be in 2 stages, since the explanation generation needs to condition on the model’s predictions. To be more specific:

-

MT-RE: Narang et al. (2020) train a multi-task T5 framework to jointly generate the prediction and explanation. The model is trained to generate an explanation with the prediction when prepending the text “explain” to the input. It can also be used for just classification by removing the hint word “explain”. The training procedure is straightforward. The authors indicate that this framework is friendly to domain adaptation, allowing it to create plausible explanations for new domains, even if the training for generating explanations is performed in a different domain.

With the same framework, Yordanov et al.(2022) study further on the few-shot transfer learning of NLE generation. They particularly investigate a scenario where transferring is from a parent task with numerous NLEs to a child task with few NLEs but a surplus of labels. By selecting pronoun resolution (WinoGrando dataset) and commonsense reasoning (ComVE dataset) as the child task (CT) and NLI (e-SNLI dataset) as the parent task (PT), they comprehensively compare four transfer learning settings: finetune on the union of PT, CT and 50 CT NLEs; finetune on the union of PT and CT, and then finetune on 50 CT NLEs; finetune on PT, and then finetune on the union of CT and 50 CT NLEs; finetune on PT, then CT, and finally 50 CT NLEs. As a result, different methods rank differently on different tasks, but leaving the finetuning of few-shot NLEs of the child task as a separate regime leads to better NLE generation quality.

-

MT-RA: Camburu et al. (2018) first describe a framework for SNLI in this mode. A classification loss and a explanation loss are jointly learned in this framework. The classifier is an MLP taking the input features. The explanation generator is a one-layer LSTM, and to be conditioned on the label, a word presenting the label is prepended ahead of the explanation. During training, the explanation generation is fed with the gold label, while for inference, the model prediction is used.

-

ST-RE: Rajani et al. (2019) propose their method in this mode. They work on the commense question answering task and train the model to provide explanation for its answer. In the first stage, the language model is conditioned on the question and all answer options in the example and trained to generate the explanation. In the second stage, a language model is used to generate explanations for each example in the training and validation sets, and then these explanations are connected to the end of the original question, answer options, and provided to another commonsense reasoning model to predict the answer. They use GPT as the language model and Bert as the commensense reasoning model. They notice that the model-generated explanations could include useful contextual information and benefit the final prediction.

-

ST-RA: Hase et al. (2020) introduce this ST-RA model in the same paper. The idea is first training the explanation generator given both the input and the label. Next they use the generator to produce an explanation for each label choice, which is then padded to the original input constructing an input sequence for each candidate label. The classifier now makes a choice among all input and explanation pairs. The authors implement all four modes with a mutli-task T5 framework (for both explanation generation and label prediction) and demonstrate that the ST-RA model achieves near-human-level LAS scores (a metric proposed in this paper measuring the plausiblity of generated explanation). They also reveal that rationalizing(RA) models perform better than reasoning(RE) models.

The framework can be more complex when external tasks or information are introduced into the procedure. Majumder et al. (2022) propose a method incorparating both extractive rationale generation and NLE generation, and enhancing the procedure with background knowledge retrieval. The whole process can be devided into 5 components: 1) extract a set of input features as the extractive rationales; 2) query the knowledge base with the extracted rationales to obtain a series of relevant knowledge fragments; 3) select the most relevant knowledge fragments from these knowledge fragments and 4) send these selected knowledge fragments to an NLE generator; 5) feeds the generated NLE into a predictor to generate the final answer. The whole framework is trained jointly, where the former 3 steps use variational learning with hidden variables and no explicit supervision signal is required. The authors show that such a framework bridges the gap between rationale extraction and NLE generation, enabling explanations to be both descriptive and faithful, largely increasing the quality of explanations.

Fact Checking Explaining as Summarization

Slightly different from the explanation generation of general classification tasks, the construction of fact checking tasks generally provides a series of fact checking reports(called ruling comments) in addition to the input claims, and the prediction task is to judge the authenticity of the claim according to the ruling comments. In this case, the explanation generation of fact checking can also be formalised as a summarisation task to generate a summary of the ruling comments which supports the model’s judgement of the claim.

Atanasova et al. (2020) regard the explanation generation as an extractive summarisation task, for which given the claim and the sequence of ruling comments, a DistillBert model learns to predict whether a ruling comment sentence should appear in the summarised explanation. They train the extractive summarisation loss jointly with the prediction (classification) loss and find that joint training could further improve the prediction accuracy compared with training the two tasks separately. Note that in the way of extractive summarisation, the learning targets are not directly the same as the gold justifications in the dataset which are human written free-texts extracted from fact checking websites. This article selects the top k sentences from ruling comments which have the highest ROUGE-2 F1 score matching the gold justification as the learning goal of extractive summarization, but this may cause a gap between the learning goal and the real explanation. Aiming at the poor coherence of explanations generated by extractive summaries, Jolly et al. (2022) propose an unsupervised method for explanation generation by post-editing extracted ruling comments. They propose an iterative edit-based algorithm, which iteratively samples 3 editing operations: insert, delete, reorder, and then find the best post-editing explanation candidate according to the defined scoring functions, ensuring the fluency, readability, semantic preservation and simplicity of the edited explanation. These edited candidates are then checked for grammar and paraphrased using external language tools. Kotonya & Toni (2020) attempt to use abstractive summarization to generate explanation, however, the model is fine-tuned on evidence ruling comments ranked by S-BERT. Therefore, there is still a gap between the training and evaluation (on human-written gold explanation).

Incorporating LLMs

In recent years, discoveries have shown that as the size of language models continues to grow, the models start to emerge with astonishing reasoning capabilities. Consequently, a substantial body of research has begun focusing on harnessing the potential of LLMs to generate explanations. Wei et al. (2022) first suggest that by prompting the LM with the Chain-of-Thought(CoT) strategy, which guides the LM firstly describe the reasoning process before generating the answer, the reasoning performance of the model can be improved. The CoT process could also be regarded as an explanation of the model’s prediction. Lampinen et al. (2022) further studied the effect of few-shot explanation on the reasoning performance of LLMs. Slightly different from CoT, they explore post-answer explanation which prompts the model to first generate predictions and then explanations, which is more friendly to inference since no complex parsing is required to obtain the answer. They evaluate the effect of several LMs under various in-context examples, explanations, instructions and conditional control settings on 40 challenging language tasks (selected from BigBench) which are newly annotated with examples and corresponding explanations. They show that explaining examples in few-shot prompts can improve the performance of LLMs and tuning on a small validation set by selecting the examples or manually refining the explanations can further make an obvious effect.

However, although LLMs have shown good reasoning ability, the reasoning processes/explanations generated by them are not always reliable and sometimes even inconsistent with their predictions. Efforts are currently underway to study the generation of more dependable and consistent explanations. Wiegreffe et al. (2022) introduce the “overgenerate-and-filter” strategy. It firstly iteratively querying GPT-3 to produce several potential explanations for each input instance. Subsequently, human annotators assess the acceptability of these generated candidates. These judgments are then utilized to train a model responsible for selecting high-quality explanations from the outputs generated by GPT-3. As this process iterates, consistently favoring higher-quality explanations than the baseline, the model can gradually improve its overall performance. Also using iterative training, Zelikman et al. (2022) filtered the model-generated explanation by the correctness of the prediction, and use the newly generate explained data to finetune the LLM itself. Specifically, prompting LLM with few-shot examples to generate explanations, and further refining the model’s capabilities by finetuning with those explanations leading to the correct answer. Repeat this process to generate the next training set using the improved model. This is a collaborative process, where the generation of the explanation improves the training data, and the improvement of the training data further improves the generation of the explanation. However, this cycle does not allow the model to solve problems that it is not able to predict correctly in the first place. To this end, for each question that the model cannot answer correctly, they generate a new explanation by feeding the model the correct answer, which enables backward reasoning — given the correct answer, the model can more easily generate a useful explanation. These explanations are then collected as part of the training data. The overall accuracy could also be improved with such a process. Given the imperfect performance of LLM few-shot learning, Zhou et al. (2023) also incoporates a small model to judge the LLM’s output. They follow the paradigm proposed by Hase et al. (2020) (ST-RA described before), at the first stage, prompt GPT-3 to generate an explanation for each candidate label, and at the second stage, the input and the explanation are sent to a small model to get the answer by prompt learning, and the label with the highest probability given its corresponding explanation is selected as the final label. The authors argue that the second phase permits the model to adapt to the flawed elucidations originating from GPT-3, while also creating opportunities to comprehend and examine the model’s behaviour due to its transparent internal workings. This work targets leveraging LLM’s explanations to get better prediction performance rather than the generation of explanation itself, and works well even though simple.

With the increasing size of LLM, even only inference can be computing expensive. Therefore, another direction of research is whether the reasoning capabilities of large models can be distilled to small models. Li et al. (2022) propose a multi-task framework to learn from the explanations generated by LLMs, which is similar to the MT-RE paradigm mentioned in (Hase et al., 2020), but for the task of explanation generation they use a CoT way where the explanation is generated before the prediction. I personally think the order of the explanation and prediction doesn’t really matter when the whole sequence is finetuned on abundant data. Different from previous methods (mentioned in the first section) trained on annotated data, they explore several ways to prompt LLM to generate explanations which can be a substitution for expensive annotation. A combined strategy that using CoT prompting for correct prediction and rationalization prompting otherwise (same as (Zelikman et al., 2022)) achieves slightly better performance on 2 of 3 QA datasets. Shridhar et al. (2022) argue that the reasoning ability of CoT relies on the huge parameter size of LLM, and distilling the reasoning ability to small models directly via CoT prompting does not work well. This study thus introduces a “decompositional distillation” method which involves two main steps: 1) By employing in-context prompting, the LLM breaks down the initial problem into multiple pairs of intermediate subproblems and their corresponding answers. 2) The decomposed reasoning approach is then distilled into two small models: the first one is a problem decomposer that learns to break down intricate reasoning tasks into simpler sub-problems, while the second one is a problem solver that learns to solve these intermediate sub-problems. On a multi-step math problem dataset (GSM8K) the performance of step-by-step distillation is 35% better than that of direct distillation of the same scale model. Wang et al. (2023) also work on CoT distillation to small models but specifically concern the inconsistency of the explanation and prediction generated by LLMs. They proposed two strategies to enhance the faithfulness of generated explanations. 1) Improve the self-consistency of LLM explanation generation through contrastive decoding of the teacher model. The principle is that explanations should be generated from answers. So for a giving question, in the process of model decoding, when masking or retaining the input of the answer, each step of searching selects the token with the highest probability increase when the answer is given. 2) Improve the faithfulness of distillation through counterfactual reasoning, which is to train the model to generate “wrong” explanations when incorrect answers are given. In this case, the reasoning shortcuts can be removed. In order not to interfere with the normal task of the model, the “counterfactual” label will be prepended to these training inputs.

Summary

In summary, recent work mainly focuses on how to use the reasoning ability of LLM to generate better explanations, or use these explanations to improve the ability of prediction. Reducing computational cost, as well as understanding and mitigating the hallucinations of LLM may be of more concern to researchers. In addition, how to more reasonably evaluate the natural language interpretation generated by the model is also a question worth studying, which will be discussed in another article if possible.