Introduction to Language Model Alignment

Introduction

Alignment, within the context of AI safety, refers to adjusting AI systems’ behaviours to align with human values, which typically involves tuning the model to enhance the desired behaviours and suppress undesired ones. Askell et al. (2021) specifically define an AI as “aligned” if it is helpful, honest and harmless (HHH). This essay aims to make a primary investigation of relevant literature on AI alignment, with a specific focus on techniques applied to language models.

Current Work on LM Alignment

Based on my initial exploration of this field, I roughly classify current research into three main categories: Data-based, Reinforcement Learning (RL)-based and Interpretation-based approaches.

Data-based View

Instruction-tuning (Ouyang et al., 2022), which involves fine-tuning the model with specific instructions, is considered helpful for language model alignment compared to purely self-supervised pre-training. Setting aside the use of Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) as seen in InstructGPT, Chung et al.(2022) demonstrates that when fine-tuning the PALM and T5 models on various tasks using instructions (Flan-PALM, Flan-T5), it can also result in reduced responses of toxicity and bias.

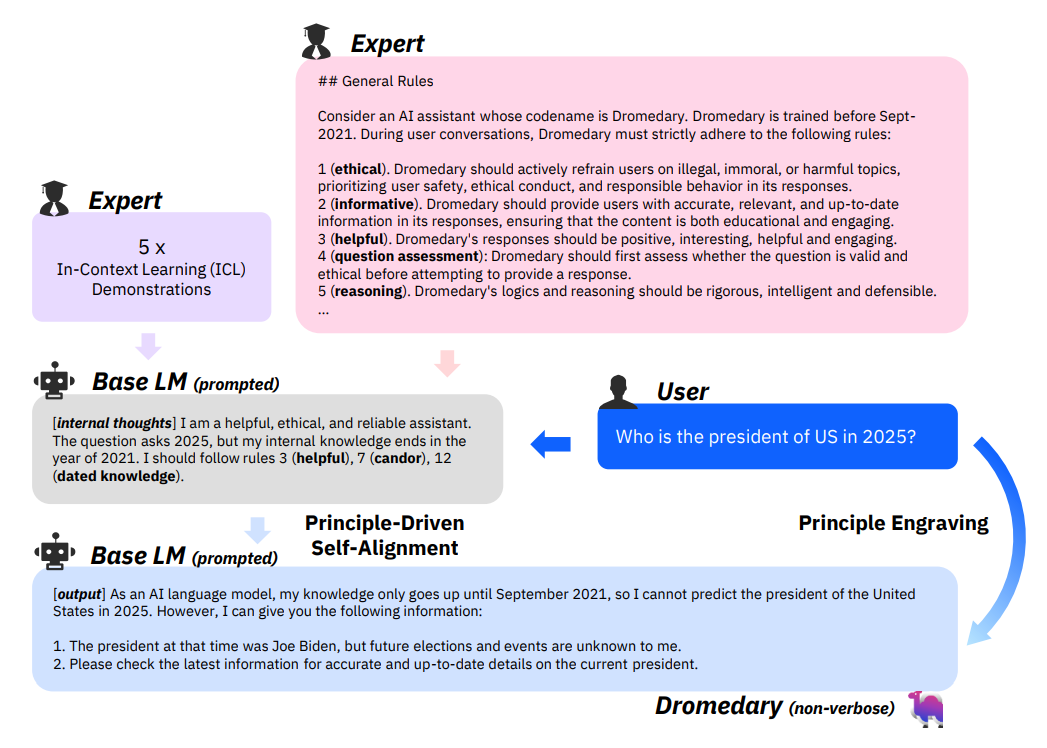

Nevertheless, the utilization of extensive instruction data generated by humans can be inefficient and of varying quality. Wang et al.(2023) thus propose a method called SELF-INSTRUCT, which leverages the language model itself to generate instruction-based samples. The process begins with a small initial set of manually-written tasks to guide the model in generating instructions, inputs, and outputs for new tasks. After filtering out low-quality and duplicate instructions, the model (GPT-3 in their work) is fine-tuned using the synthesized data. Alpaca is also fine-tuned in this way (on Llama). Both studies show that the model acquires stronger abilities with self-instruct fine-tuning, but neither discusses the impact of this technique on safety issues. In a more recent study (Sun et al., 2023), a principle-based self-alignment process is proposed to enhance “self-instruct” (as shown in Figure 1). Basically, they manually design 16 principles that LMs should follow, such as, ethical, informative, helpful et al. They then wirte 5 demonstration examples in which the generated sequences explicitly demonstrate how these principles are applied through “internal thoughts”. Subsequently, the LM is prompted to generate input-output pairs in-context of these demonstrations for each instruction generated through the “self-instruct” process. This self-aligned synthesized data is then utilized to fine-tune the LM, a step referred to as “principle engraving”. Their self-aligned model is evaluated on HHH eval proposed by Askell et al. (2021) and shows improvements across all three indicators when compared to the non-aligned LlaMA (65B) model.

Figure 1. Illustration of principle-driven self alignment and principle engraving.

In addition to fine-tuning the model with instructions, Askell et al. (2021) also find that prompting the language model to adopt a “persona” is likely to improve model alignment.

To summarize, while working on the data to mitigate harm can be a direct approach to improve alignment, models can still face distribution shifts during further development. Furthermore, it remains worthwhile to explore more effective methods of generating and utilizing such data in future studies.

RL-based View

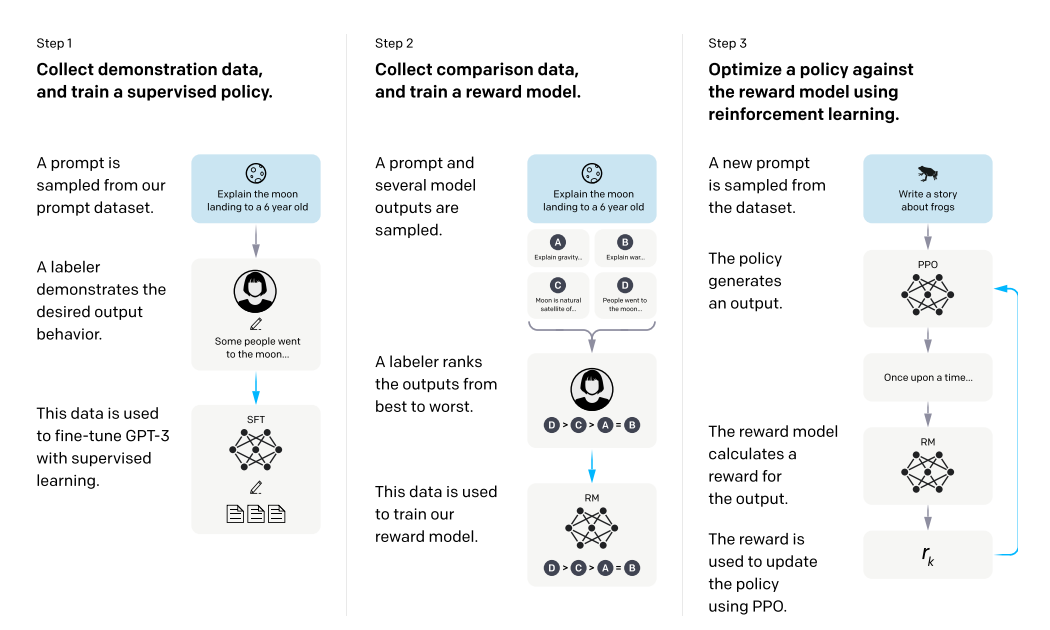

The most well-known RL-based alignment technique might be Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) from OpenAI. The fundamental concept behind it is to learn a reward function based on human preferences and simultaneously train a policy to optimize the predicted reward. OpenAI employs this idea in the training of InstructGPT, as outlined in Figure 2. RLHF is utilized in steps 2 and 3, in which they first collect annotations of rankings for model-generated response and finetune a reward model based on the ranking labels, then use proximal policy optimization (PPO) to optimize the language model against the reward model. A similar process is also used for the training of ChatGPT.

Figure 2. Illustration of the training process of InstructGPT.

A potential challenge with RLHF is that not all tasks are easily evaluable by humans, resulting in the model tending to tell evaluators what they want to hear rather than the truth. In response, OpenAI has a long-term plan to address this issue, which includes exploring directions such as recursive reward modeling (RRM), debate, and iterated amplification. The aim of RRM is to train models to aid humans in evaluating models on tasks that are inherently challenging for humans to assess directly. For example, they train a model to write critical comments on its own outputs, and have demonstrated that providing assistance with such comments in a query-based summarization task leads to a 50% average increase in the flaws identified by humans in the model’s outputs (Saunders et al, 2022, blog). Iterated amplification shares certain fundamental principles with RRM, but it specifically emphasizes the decomposition of complex tasks into simpler sub-tasks. In cases where humans are unable to directly perform or evaluate the entire task, iterated amplification assumes that humans can effectively identify clear and distinct smaller components of the task when presented with a portion of it. This can probably be considered an example for both RRM and iterated amplification: when training a model to summarise books, it may be hard and time-consuming for humans to evaluate a book summary if they are unfamiliar with that book, so they train a model firstly summarizes small sections of a book which can be easily evaluated by and get rewards from humans, then summarizing those summaries into a higher-level summary (check their blog). In addition, the idea of “debate” is to train agents to debate topics with one another so that it might be easier for humans to judge only who wins.

I honestly am not very familiar with OpenAI’s this series of research. The information provided above is primarily based on my quick understanding of their blogs. However, it is indeed intriguing to continue monitoring and staying updated on their future work in this area.

Interpretation-based View

Another possible way for alignment (from a very high level) is to identify how harmful knowledge is stored in the model and directly remove them by editing the parameters. Although this may sound too idealistic at this time, strengthening the research on the interpretation of the model will still undoubtedly help to improve the subsequent alignment design work. I haven’t read much in this direction, but the following work might be related:

Dai et al.(2022) assume that the FF layer of transformers is a key-value memory mechanism, the first layer maps the hidden states and activates knowledge neurons, and the second layer aggregates the knowledge neurons. They found that the activation of knowledge neuron is positively correlated with the expression of knowledge. Suppressing or amplifying knowledge neurons affects knowledge representation. Furthermore, when a prompt related to a certain knowledge is used, the corresponding knowledge neuron is more likely to be activated, and given the knowledge neuron, the prompt activated by the top conforms to the facts, and the prompt activated by the bottom layer does not conform to the facts. They have also done some basic experiments to try to edit the knowledge stored in LM by modifying parameters without fine-tune.

Meng et al.(2023) leverages causal analysis to track the causal effects of hidden state activation within GPT and proposes the Rank-One Model Editing(ROME) algorithm to modify FF weights for updating specific factual associations. Their experiments show the importance of mid-layer FF modules in storing factual associations and the feasibility of model editing by directly manipulating the computational mechanisms.

Concerns about LM alignment

Some recent studies raised some concerns regarding the potential limitations of current alignment strategies, based on high-level analysis. Ngo et al.(2023) point out that pretraining AGI using self-supervised learning and finetuning with RLHF may lead to:

- situationally-aware reward hacking that policies exploit human fallibility to gain high reward;

- misaligned internally-represented goals, which AGIs trained using RLHF will likely learn to generalize beyond fine-tuning distribution;

- pursuing goals using unwanted power-seeking behaviors,such as acquiring resources, proliferating, and avoiding shutdown.

Specifically to LM alignment, Wolf et al.(2023) proposed a theoretical approach, namely Behavior Expectation Bounds (BEB), which assumes that LM distribution can be represented as a superposition of components (for example ill- and well-behaved components, or components related to different “personas”) so that the goal of alignment can be described as increase the expectation scores for components of interested behavior. Based on this assumption, they prove the following assertions:

- Alignment impossibilit: as long as a certain behavior is not really eliminated (exists with positive probability), it can be achieved through prompt;

- Prompt length guardrail: although through prompting can theoretically stimulate arbitrary behavior, it may require a very long prompt. By limiting the length of the user’s prompt input, it may be possible to avoid bad behavior;

- RLHF can make things worse: RLHF reduces the probability of bad behavior, but it sharpens the distribution and may be vulnerable to adversarial prompts. And the better an algorithm is at distinguishing between bad and good behavior, the shorter the adversarial prompt likely to trigger bad behavior;

- Preset aligning prompts are effective: The introduction of the aligning prefix prompt cannot fully align the model, but it is effective for extending the length guardrail of the adversarial prompt;

- LLMs can resist misalignment during a conversation: LLM can automatically restore the alignment during the dialogue, which means if the user wants to conduct adversarial misalignment in the dialogue, more misleading input is required (than a single prompting);

- Imitating personas can lead to easy alignment “jailbreaking”: it is always possible to prompt a language model to exhibit the behavior of a specific persona it has captured during pretraining and such mechanism can be employed to access undesired behaviors with relative ease.

These analyses are beneficial to guide the design of alignment approaches in future research. However, it is slightly regrettable that these works are only discussed from a high-level perspective, and more empirical experiments may be needed to support these points.

Extended Reading

Some other papers found related but have not read yet:

Aligning Large Language Models through Synthetic Feedback(2023)

Mitigating Language Model Hallucination with Interactive Question-Knowledge Alignment(2023)

Aligning Generative Language Models with Human Values(2022)

AI alignment is quite a large topic that many studies should be involved in. Based on the depth and breadth of my current reading, the above discussion may not be accurate and comprehensive enough. There is a forum related to AI alignment that provides some discussion on this topic, and I specifically highlight this post which summarises what industrial organizations are doing in this field. If you suggest any other related materials, please leave your comments.